In the scorching summer of 2010, the Utah desert stretched endlessly like a sun-bleached cathedral of rock and silence, a place where the land itself seemed to hold secrets too heavy to tell. It was here, among the jagged mesas and forgotten uranium mines, that two promising young Black academics from Atlanta disappeared without a trace.

Elijah Sinclair, a geology PhD candidate fascinated by the geological scars of the Cold War, and his wife Nia, a gifted photographer whose work captured beauty even in desolation, had traveled west to study abandoned mines, poisoned earth, and the silent stories carved into stone. Their final message was a poetic email to Elijah’s father, Samuel, filled with excitement about the desert’s haunting beauty and Nia’s striking photos, but buried in the notes was a chilling aside: a local deputy, described as an old-timer fiercely territorial about the mines, had warned them away from certain shafts. Samuel, a retired history professor who understood the danger of both deserts and people, felt unease when he read those words.

He replied with a father’s wisdom, warning them that the most dangerous formations aren’t made of rock and asking them to call him on Friday. That call never came. Days passed, phones rang unanswered, and dread grew heavier by the hour. When authorities were finally contacted, they responded with politeness but little urgency. Soon after, the Sinclairs’ rental car was found abandoned at a remote trailhead, keys still inside. The official search, led by Sheriff Brody Wilcox and his deputy Dale Lteran, was brief and hollow. A handful of volunteers in dusty pickups combed the canyons, but after only two days it was called off. Wilcox dismissed them to reporters as unprepared city kids who wandered into the Devil’s Maze, a treacherous labyrinth of sandstone canyons, and succumbed to the desert’s merciless grip.

The story was wrapped neatly with a paternalistic tone, but Samuel stood quietly at the edge of the crowd, grief sharpening into fury. He knew a lie when he heard one. For the next eight years, Samuel’s life became a relentless quest for truth. His study turned into a shrine of loss, lined with maps, satellite images, clippings, and notes. While the world moved on and even his wife Eleanor’s health faltered until grief finally claimed her life, Samuel refused to let go. He was a historian; he believed in evidence and the patient power of facts to erode even the hardest stone.

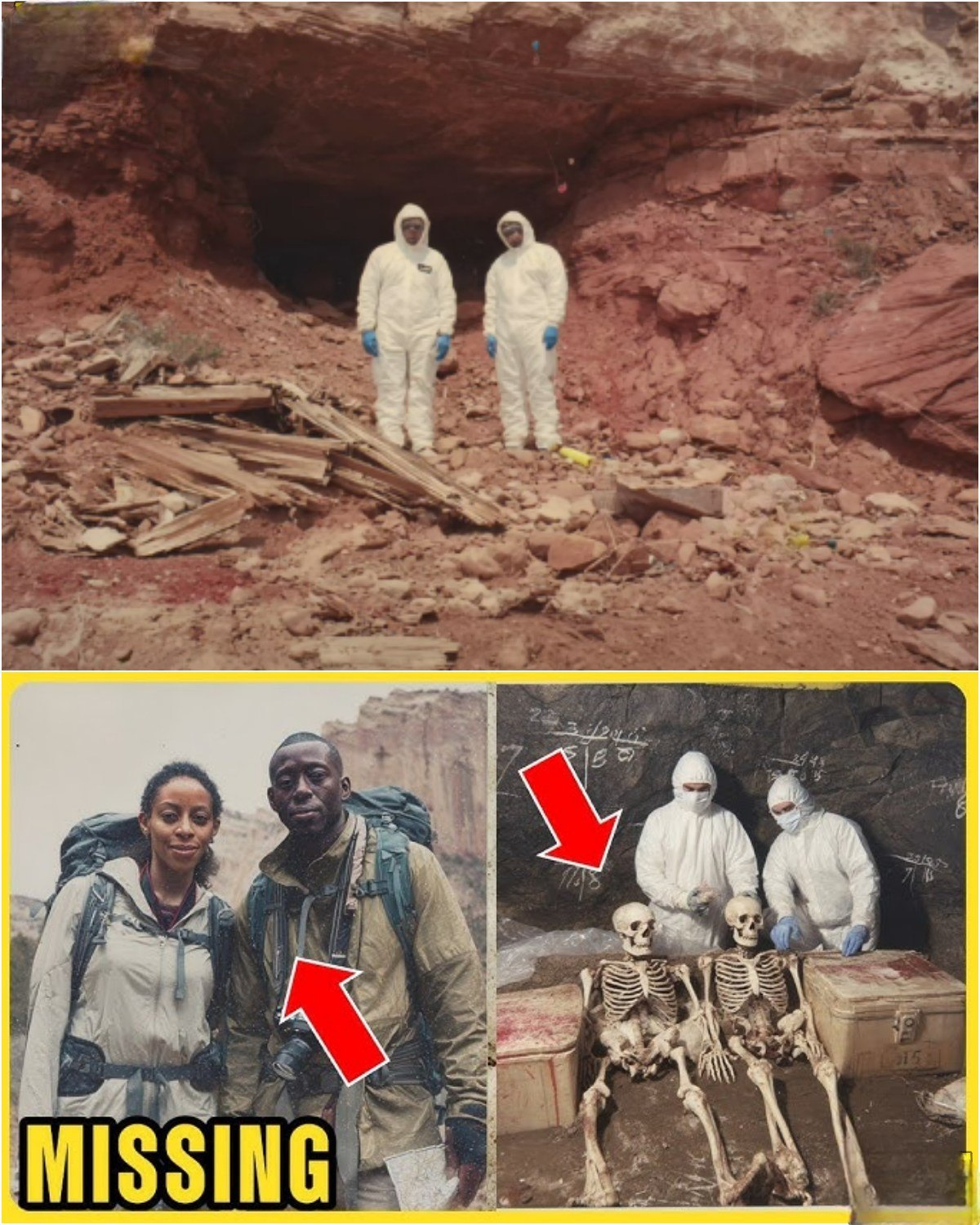

The desert, however, kept its silence until the summer of 2018, when a government crew tasked with sealing abandoned mines detonated explosives at the mouth of a forgotten shaft. When the dust settled, a gaping hole revealed a grim tableau inside: two skeletons, seated side by side on an ore crate, eerily calm in posture as if posed for a final portrait. Their clothes, though faded, were modern. Word spread quickly—the missing Sinclairs from Atlanta had been found. Detective Kate Riley of the Utah Bureau of Criminal Investigation took over the case.

Methodical and unafraid to challenge long-standing narratives, she called Samuel personally and promised to reopen the investigation from scratch, following the evidence wherever it led. For the first time in eight years, Samuel heard truth in a law officer’s voice. The mine itself told a chilling story. The couple had not died naturally in the shaft. Their bodies had been deliberately placed and posed. The mine entrance had been sealed, not by time or erosion, but by explosives—professional, precise, and intentional. Toxicology confirmed both Elijah and Nia had ingested lethal levels of arsenic, enough to kill within hours. There were no bullet wounds, no fractures, only poison coursing through their blood. This was no accident; it was murder. Riley and her team dug into the region’s history and discovered arsenic’s use in illicit gold extraction.

The Sinclairs, with their curiosity and expertise, had likely stumbled upon an illegal modern mining operation worth a fortune. They hadn’t just uncovered a Cold War relic; they had walked into someone’s secret empire. The killer had motive—greed. He had the means—poison and explosives. And he had opportunity—the trust of two unsuspecting outsiders. Riley reexamined the original case and found the trail pointed to within the sheriff’s department itself. Wilcox clung stubbornly to his old story, while Dale Lteran, now county sheriff, appeared helpful and cooperative but subtly pushed suspicion toward a dead prospector named Hemings. Yet the forensic trail betrayed him. The explosives used to seal the mine were traced to government-issued blasting caps signed out under Lteran’s name just days after the Sinclairs disappeared, supposedly for a “beaver dam removal” project.

His signature in the dusty logbook was the damning final piece. Confronted, Lteran confessed. The Sinclairs had discovered his illegal gold operation, and in fear of exposure, he poisoned them, staged their bodies, sealed the shaft, and orchestrated a sham search and cover-up. The desert’s silence and the sheriff’s prejudice had been his accomplices. A month later, Samuel stood before the sealed mine, now marked with a simple bronze plaque. Detective Riley placed Elijah’s geology hammer in his hands, recovered from the scene.

Tears filled his eyes as he whispered, “You gave them back their names. You gave them back their dignity.” Riley nodded solemnly and replied, “It was the evidence they left behind—and the evidence he left—that found them.” Though Samuel’s loss would never fully heal, the silence of the desert had been broken. The lie was undone, and the truth, buried for eight long years beneath stone and prejudice, had finally come into the light. The Utah desert may never forget, but in time, justice found its voice, proving once more that the truth, no matter how deeply buried, can never stay hidden forever.