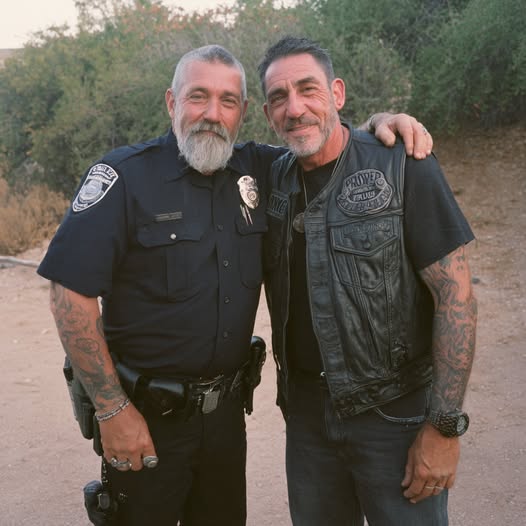

I was fired as a cop for helping a biker fix his broken taillight on Christmas Eve instead of arresting him, and twenty-three years of spotless service ended because I gave a father trying to get home to his kids one of my patrol car’s spare bulbs rather than impounding his motorcycle and wrecking his family’s holiday. The chief called it “aiding a criminal enterprise,” even though the man’s only offense was a burned-out taillight and an empty wallet.

When that biker heard I’d been terminated, he did something that made a tough man like me cry and taught me what brotherhood means in the biker world. His name was Marcus “Reaper” Williams, and despite the road name and the Savage Souls MC patches, he was an exhausted factory worker coming off a sixteen-hour shift, just trying to reach his kids. I stopped him around 11 p.m. on December 24 after a string of BOLO alerts about the Savage Souls had us expecting drugs or guns; instead I found a lunch box, a child’s drawing labeled “Daddy’s Guardian Angel” taped to his gas tank, and real panic in his eyes. He kept his hands visible and told me he’d just finished a double at the steel plant and hadn’t seen his kids awake in days.

His taillight was dead, and by policy I should have cited him and impounded the bike—no exceptions for “one percenters,” the chief had said—but that drawing hit me hard; my own daughter used to leave me sketches when I worked doubles. I told him to pop the seat, grabbed a spare bulb from my repair kit, swapped it in under five minutes, and wished him a Merry Christmas, figuring the relief on his face was worth any grief I might catch. Three days later I was in Chief Morrison’s office staring at a photo of me fixing that taillight, and my explanation—no priors, coming from work, Christmas Eve—meant nothing. He barked about explicit policies on gang members, accused me of giving city property to a criminal organization, and called it theft and material support.

I was suspended, “investigated,” and fired on January 15; the letter said “theft of municipal property” and “conduct unbecoming,” and at fifty-one, blacklisted from every department within a hundred miles, I was unemployable in the only job I’d ever known. Then it got interesting. At Murphy’s Bar, nursing my third whiskey and rehearsing how to tell my wife we might lose the house, the doorway filled with leather—dozens of Savage Souls with Reaper at the front. My hand went to where my duty weapon used to ride. Reaper raised his palms: “Easy, Davidson. We’re here to help.” He slid me a tablet showing a viral article about my firing and said they hadn’t leaked it, but the chief was spinning me as corrupt.

“We know you’re clean,” he said, and his brothers pulled folders: in twenty-three years I’d arrested forty-seven Savage Souls, and every single one said I treated them fair—no planted evidence, no excessive force, no bogus charges. They reminded me of Tommy Briggs, the guy I arrested in ’09 whose kid I drove to school when there was no one else. Then they opened another folder: photos of Morrison shaking hands with men tied to the Delgado cartel, proof he’d been taking their money while targeting bikers as easy headlines.

Finally, Reaper produced a flash drive with security footage from December 24, 2014: Morrison, then a lieutenant, beating a handcuffed suspect—Reaper’s brother Danny—who died two days later; the official report said he fell while fleeing. I filed a wrongful termination complaint and showed up to the February 1 city council meeting expecting a handful of supporters; instead, forty-seven Savage Souls and their families packed the room, joined by citizens I’d helped over the years—the teen I talked off a bridge, the domestic violence survivor I protected, the homeless vet I fed. When the video played, the chamber erupted. State police arrested Morrison, the FBI followed the Delgado money, and seventeen officers went down with him. I was reinstated with full back pay, promoted, and the city settled my suit, paying off my mortgage.

On my first day back I responded alone to a bar fight; the Savage Souls stood between me and a group of drunk college kids until backup arrived, and the punks came quietly. Later Reaper told me his daughter had been in the hospital that Christmas Eve with leukemia; that taillight fix let him reach her bedside, and she’s now in remission and wants to be a cop. The three-dollar bulb that nearly ended my career hangs framed in my office next to a photo of me and forty-seven bikers delivering toys at the children’s hospital. Morrison got twenty-five to life, the Delgado pipeline was broken, and the Savage Souls are still outlaws, still rowdy, and still the first to form a wall behind me when things turn dangerous. Sometimes brotherhood outlasts badges and patches, sometimes doing right beats following rules, and sometimes a three-dollar taillight bulb changes everything.